Downloadable Images

The images in the bookSt. Paul’s Outside the Walls: A Roman Basilica from Antiquity to the Modern Era (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

for which I have the rights are downloadable here.

Hover over image to see larger versions and click thumbnails below to download high-resolution tif files.

For images in the introduction and in chapters 1-3, see below

For images in chapter 4-6, click here

For images in chapter 7, the epilogue and appendix, click here

Return to main page

|

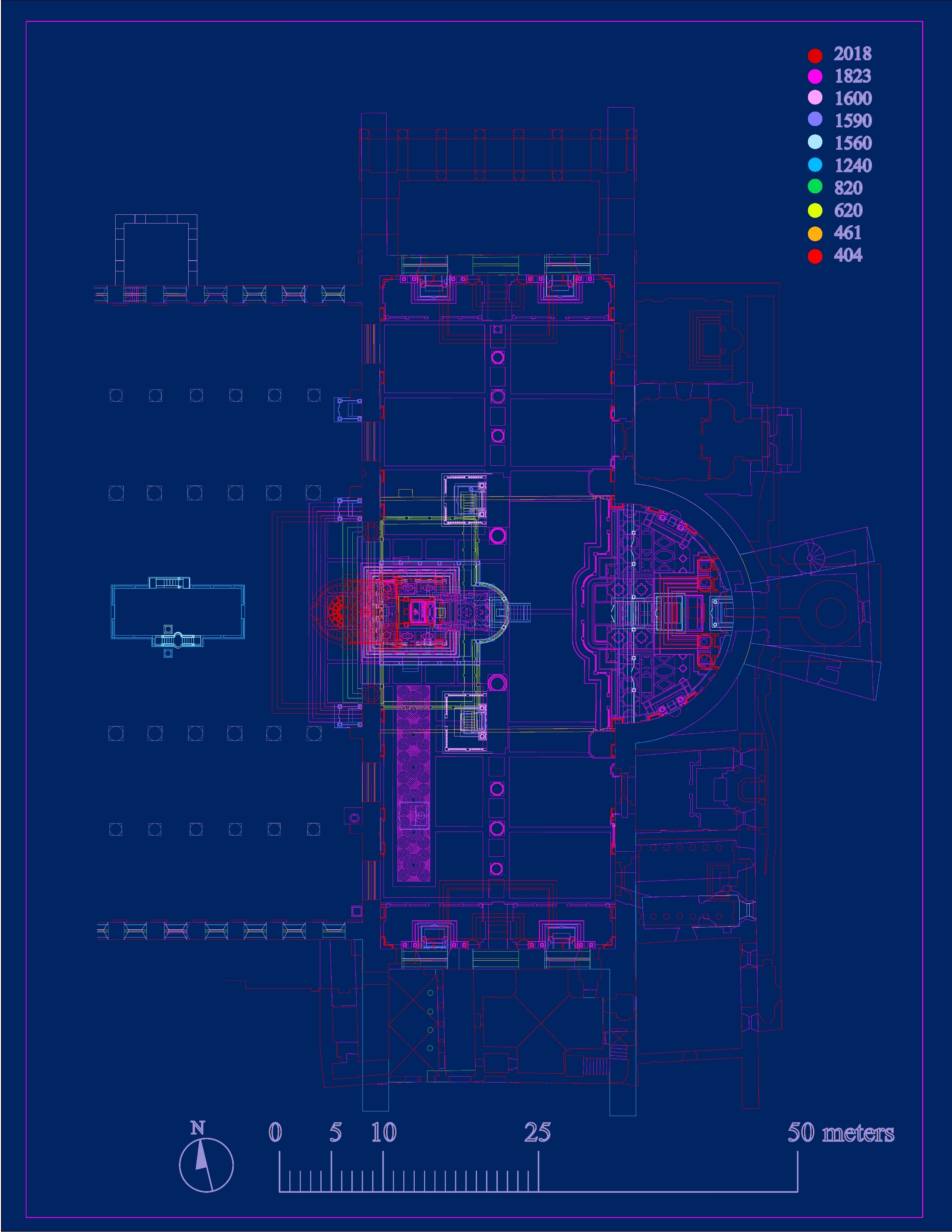

Fig 0.10 Composite plan of St. Paul’s apse, transept, and the eastern end of the nave (404-2018). The color-coded chronology does not indicate when a feature was built – that is often unclear; rather, it indicates when a feature first appears in one of the ten digital models that were produced. The frequency of changes at St. Paul's should nonetheless be apparent. Models and image by Evan Gallitelli. |

|

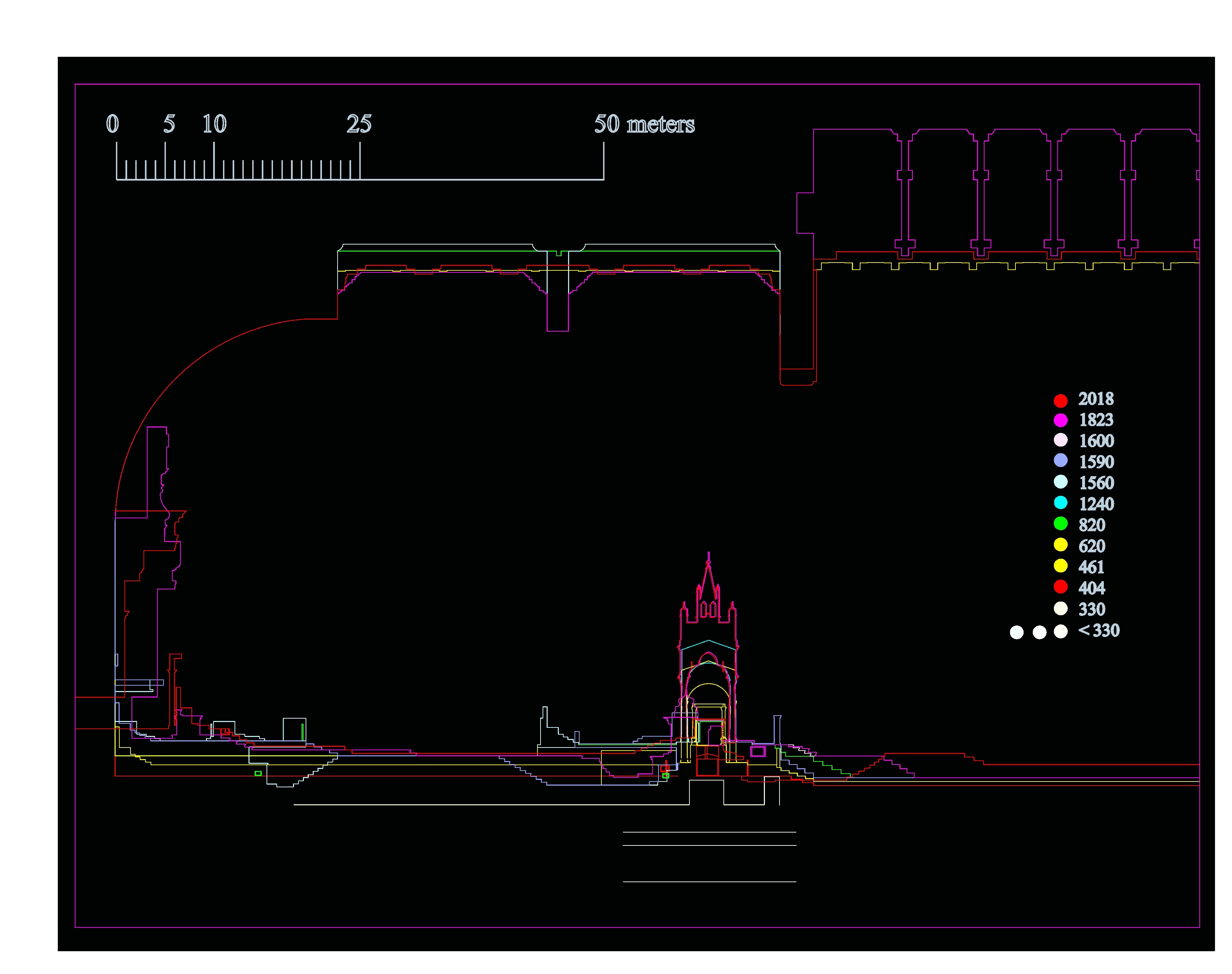

Fig. 0.11 Composite section cut E/W through St. Paul’s apse, transept and the eastern end of the nave (until 2018). The color-coded chronology does not indicate when a feature was built – that is often unclear; rather, it indicates when a feature first appears in one of the ten digital models that were produced. Models and image by Evan Gallitelli. |

.jpg)

|

Fig. 0.12 Reconstructed plans and sections of St. Paul’s apse, transept, and the eastern end of the nave (404-2018). Models and image by Evan Gallitelli. |

|

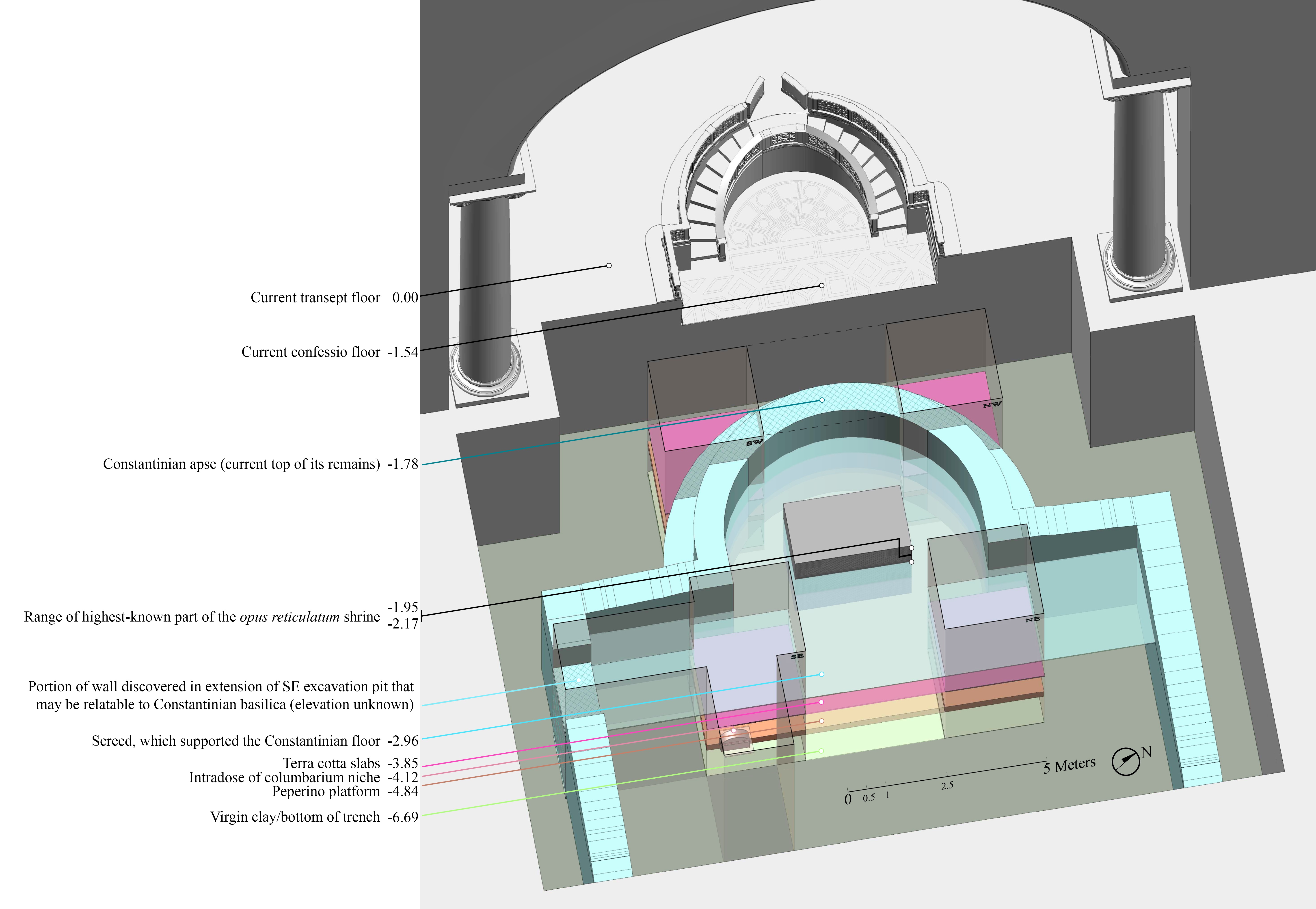

Fig. 1.4 Composite reconstructed view of the finds and stratigraphy around Paul’s grave as known through nineteenth-century excavations reported by Luigi Moreschi (trenches labeled NE, SE, NW, SW) and Paolo Belloni (cross-hatched apse of the Constantinian basilica). The drawing reveals the discoveries made beneath the current transept floor during the excavations of 1838, 1850–1854, and 2002-2006. Stratigraphic levels are all derived from summary reports made by archaeologists, the most recent and updated of which was published in 2009. Incorporated here are: (1) four vertical trenches/pits documented in the notebook of Luigi Moreschi, when the foundations for the alabaster columns of the nineteenth-century baldachin were dug around the main altar; (2) a plausible outline of the Constantinian basilica that included a hatched portion of its apse, which represents what is known to us, and the body of the building that may be delimited by another portion of hatched wall discovered – at an unknown elevation – in a southern extension of the SE trench; (3) layers of materials that include the screed upon which the Constantinian floor was laid, a stratum of terra-cotta slabs, another of peperino stones, and – at the bottom of the four trenches – a layer of virgin clay; (4) a structure of opus reticulatum known from a drawing in Vespignani’s sketchbook (Figure 1.6) along the chord of the apse. Its full elevation can only be approximated, but it probably emerged above the Constantinian floor as discussed in Chapter 1. |

|

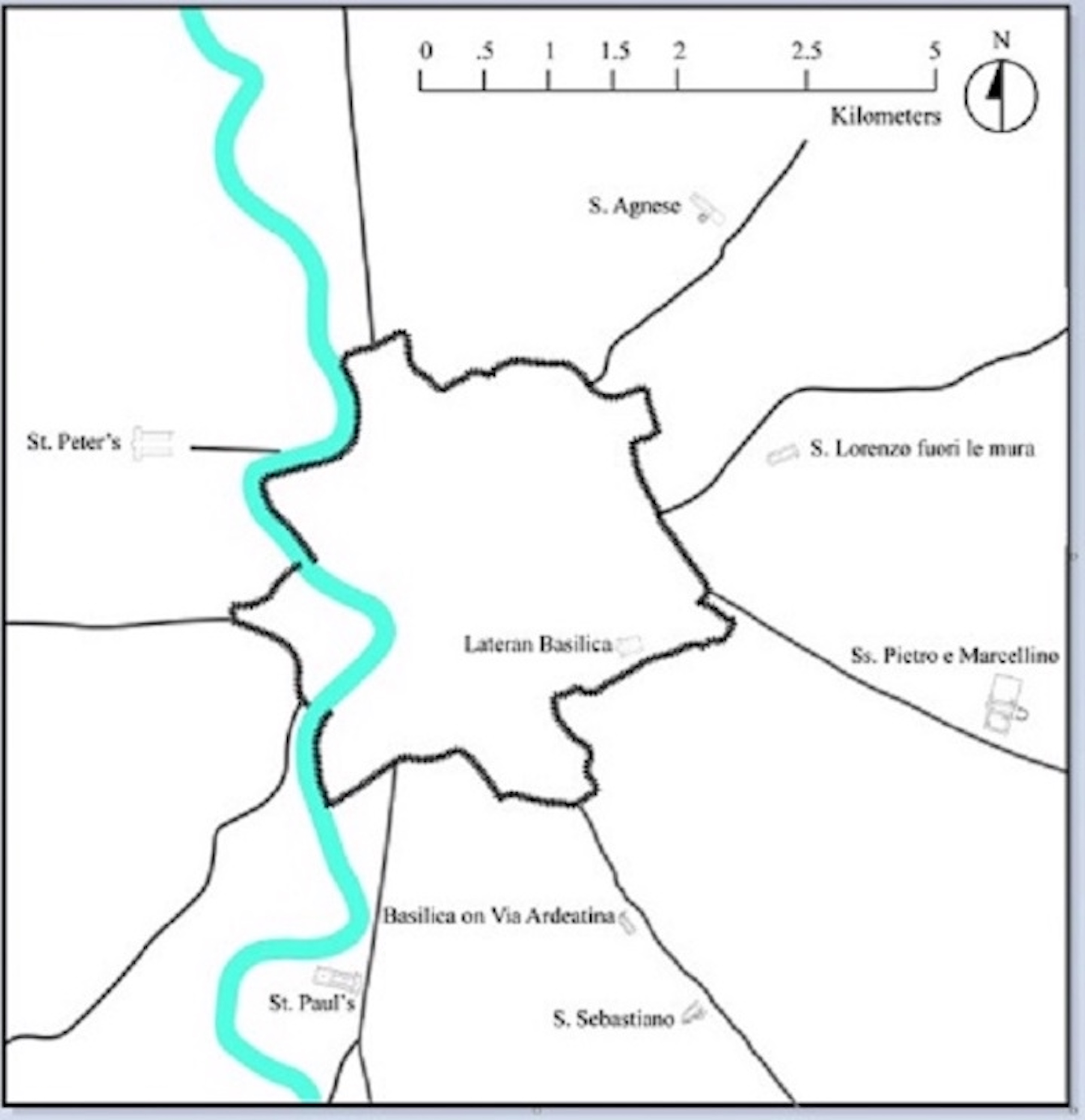

Fig. 1.8 Map of Rome and its surroundings with important early Christian basilicas, ca. 400. Note: buildings are larger than in reality. Image by Evan Gallitelli. |

|

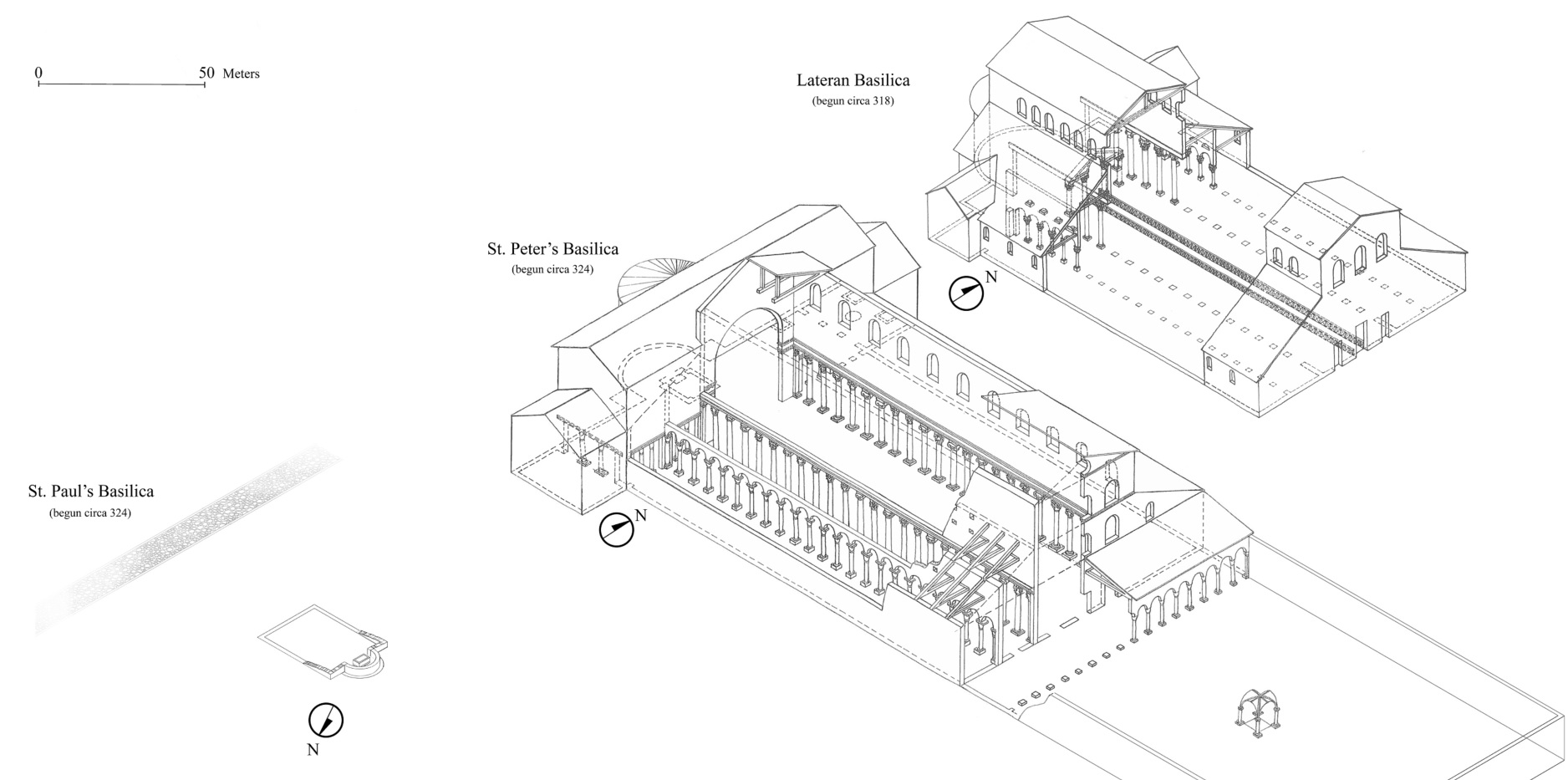

Fig. 1.9 Comparative view of the Constantinian basilicas at St. Paul’s, St. Peter’s, and at the Lateran. Model of St. Paul’s by Evan Gallitelli. Image by Evan Gallitelli includes drawings by Konstantin Brandenburg published in Hugo Brandenburg’s Ancient Churches of Rome from the Fourth to the Seventh Century (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), fig. 1. The Constantinian basilica is known only in the vaguest of terms. The apse, possibly a portion of southern wall, and the level of the pavement are the only evidence, as indicated in the discussion of Figure 1.4. The length of the Constantinian basilica is speculative and determined by the width of the transept of the Theodosian basilica, which many scholars suggest completely encased the earlier structure. This hypothesis informs the length of the Constantinian basilica depicted in Figures 2.1. The Constantinian basilica opened toward the east, where the Ostian Road ran at the foot of Paul’s crag. |

|

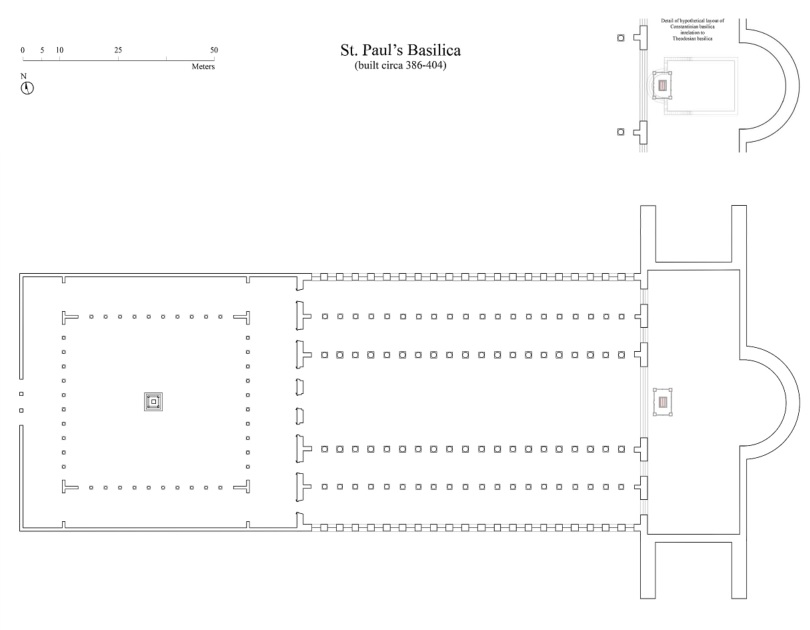

Fig. 2.1 Reconstructed plan with a detail of its possible relation to its Constantinian predecessor, ca. 404. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. These plans of St. Paul’s are largely a digital trace of Alippi’s survey published in 1815, though any accretions subsequent to the building’s inception were excluded. The western face of the atrium is speculative as no evidence of the original condition survives. |

|

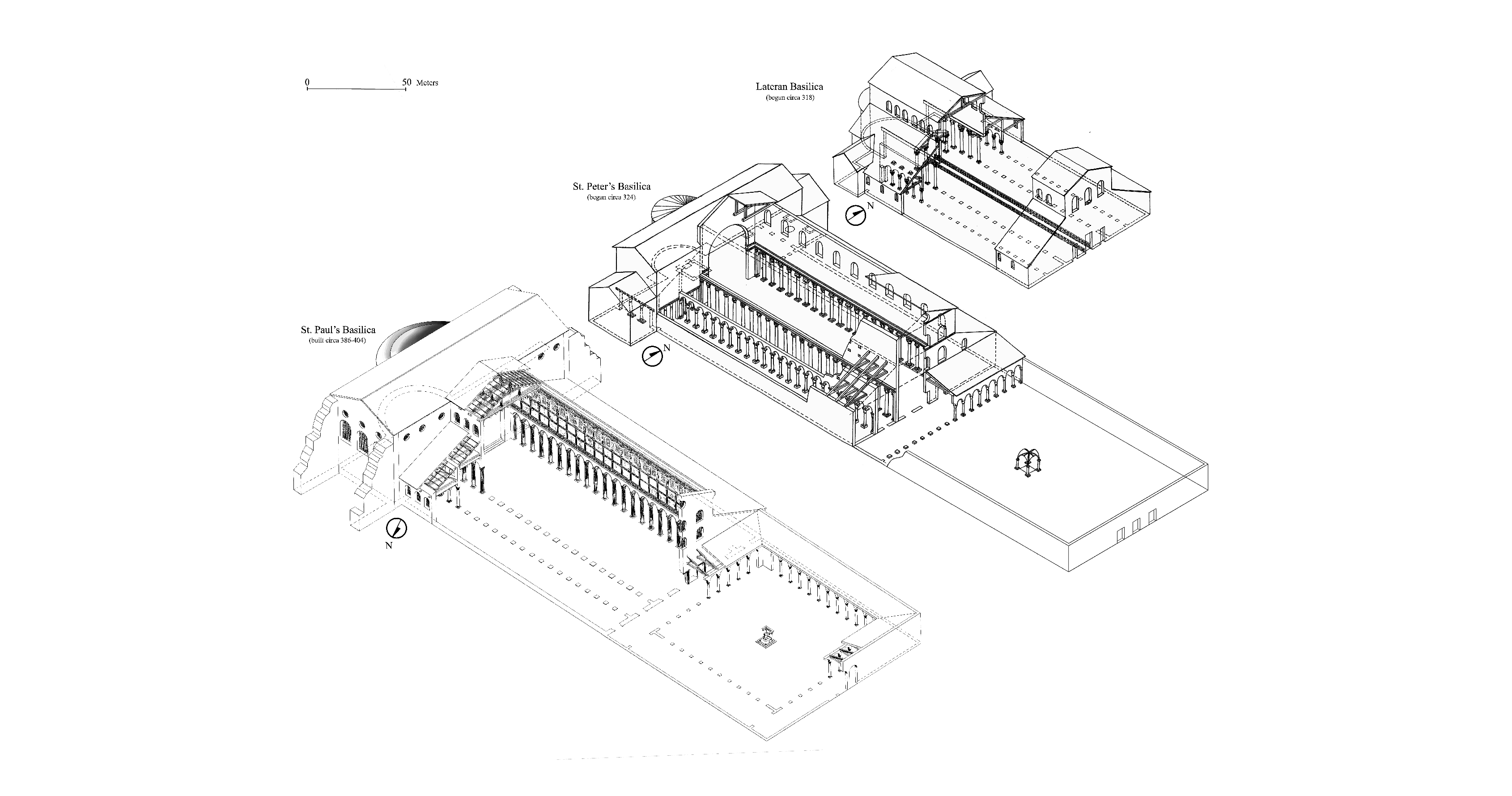

Fig. 2.2 Comparative view of the Constantinian basilicas of St. Peter and at the Lateran, alongside the Theodosian basilica of St. Paul. All are depicted at the same scale. Model of St. Paul’s by Evan Gallitelli. Image by Evan Gallitelli includes drawings by Konstantin Brandenburg published in Hugo Brandenburg’s Ancient Churches of Rome from the Fourth to the Seventh Century (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), fig. 1. These plans of St. Paul’s are largely a digital trace of Alippi’s survey published in 1815, though any accretions subsequent to the building’s inception were excluded. The western face of the atrium is speculative as no evidence of the original condition survives. |

|

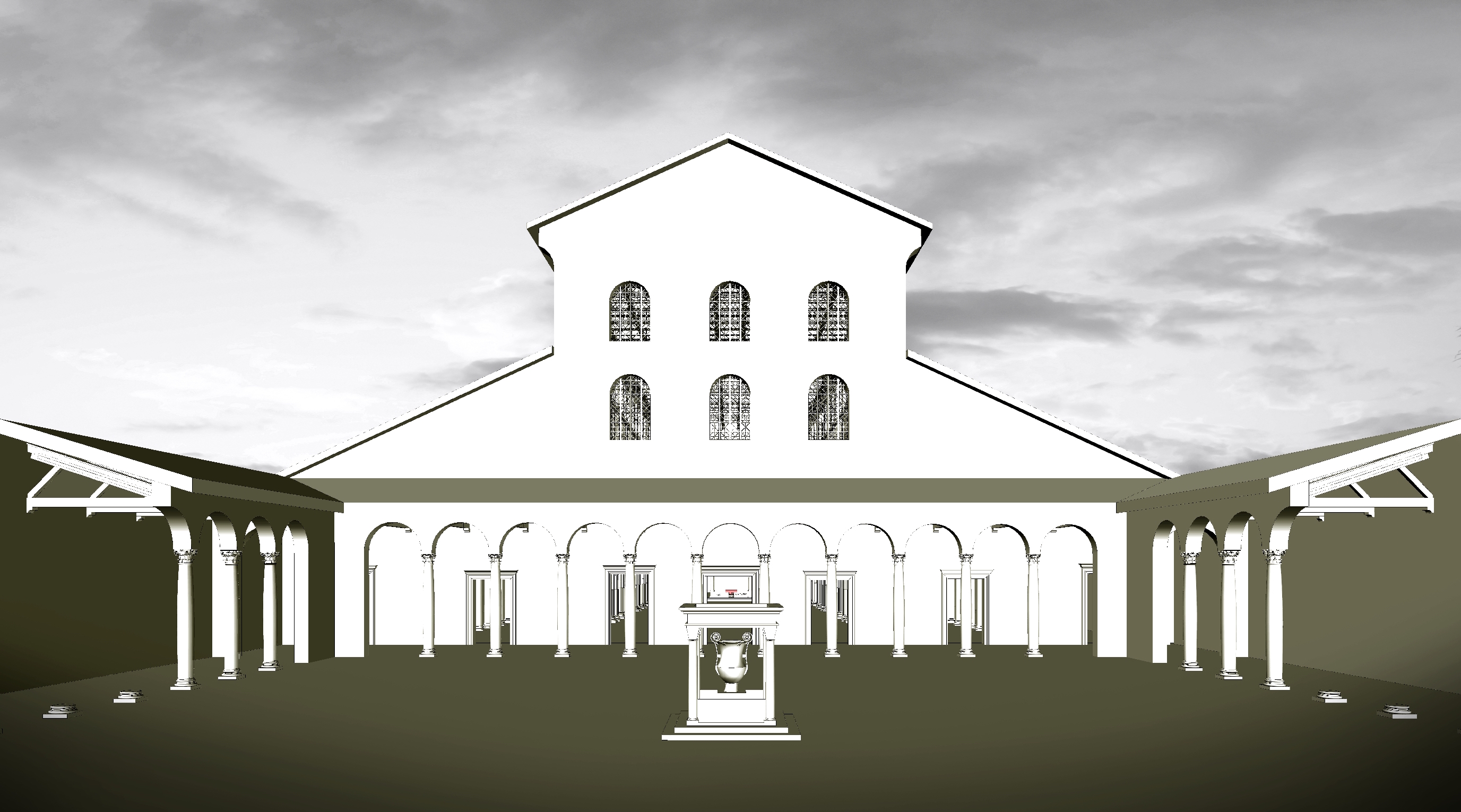

Fig. 2.5 Reconstructed view of the Theodosian atrium, ca. 404. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. The heights of the columns of the atrium were determined by the height of the columns represented in the elevation surveyed by Alippi (Fig. 7.13). The presumption is that the original narthex columns were reemployed in the Specchi / Canevari reconstruction of the 1720s and some remained undamaged by the collapse of the vault. The capitals are those that Brandenburg believes to have belonged to the atrium and are sized to correspond with the dimensions of those known fragments. The window mullions of the façade are speculative and based on those from a few decades later at Santa Sabina. The appearance of the cantharus, or central fountain, is hypothetical but based on others believed to have been in late antique courtyards. |

|

Fig. 2.9 Reconstructed view of the interior from the main door, ca. 404. The imagery in the apse is hypothetical. Model by Evan Gallitelli, lighting and rendering by Ty Austin. The view is from the perspective or a person standing at the central threshold in 404 CE, the likely year of the basilica’s dedication. The presence of gilded coffering in the nave and side aisles is based on evidence discussed in Chapter 2; however, the pattern of the coffers is hypothetical and based on modern reconstructions at the fourth-century Basilica in Trier, Germany. The frescos along the northern and southern (i.e. left and right) walls are those known from seventeenth-century watercolors preserved at the Vatican Library, so they do not represent the correct imagery present in the Theodosian basilica; however, there is every reason to believe the northern, southern, and triumphal arch walls reflected similar subject matter as these later depictions. The stucco decorations around the arcades appear to be original; while, I argue, the papal portraits only extended on the southern side. The impression of three dimensionality of the frames is a mistake. The column capitals – derived from photogrammetry – alternate, as per Brandenburg’s tenable hypothesis. The full extent of the apse is visible from the central threshold, because the triumphal arch was not yet reduced in width or height. The presence of columns beneath that wider, original arch is unlikely, but possible. The structure enclosing Paul’s sarcophagus is speculative, but based on a scholarly reconstruction of one present at St. Peter’s and justified by the thick concrete foundation that was poured into the curvature of the preceding Constantinian apse, presumably to support a heavy structure. The position of the inscription slabs (probably dedicatory) around the enclosure that originally read “Paulo Apostolomartyri (and presumably the name of the dedicator)” is tentative, but it replicates the epigraphic style and the original dimensions of the slabs known to have been reemployed as an altar table by Leo the Great. The imagery of the apse is completely uncertain, though the original was probably a source for the later iteration shown in black and white here. The imagery of the triumphal arch is more likely to be accurate, though some adjustments would have been made to repair fissures and cover new portions of wall added with Leo’s arch. |

|

Fig. 2.14 Measurements and modularity of the Theodosian basilica. Model by Evan Gallitelli. Image by Evan Gallitelli, based on drawings by Marina Docci, San Paolo (2006), figs. 30 and 32. |

|

Fig. 2.16 Reconstructed section through the Theodosian basilica indicating the possibility of a suspended ceiling in the side aisles. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. This image demonstrates how the side aisles could have been covered by a suspended coffered ceiling. The relief arches above the side aisles and the height of the nave arcade are based on Alippi’s elevations and sections (for instance Fig. 2.22). These reveal that they were designed by their builders in such a manner as to not impede suspended ceilings in both the inner and outer aisle. |

|

Fig. 2.21 Reconstructed view of natural lighting conditions in the Theodosian transept. Model by Evan Gallitelli, lighting and rendering by Ty Austin. The round windows in the western wall of the transept were depicted asymmetrically by Alippi in his elevation of the façade. We can only assume it to be correct, so the model has asymmetric windows in the transept as odd as that may appear, today. For reasons explained in Chapter 2, there are no other windows on the western transept wall. Even without then, the space did not lack for light. The light renderings assume some form of glass in the window panes, but it is unclear what material was originally there. |

|

Fig. 2.22 Pietro Ruga (etcher), Andrea Alippi (surveyor), Carlo Ruspi (designer), II. Spaccato della Basilica Ostiense sulla linea B, from N.M. Nicolai, Della basilica di S. Paolo, plate 2, etching, 1815. |

|

Fig. 2.23 Reconstructed section looking toward the south, ca. 404. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. These are longitudinal sections based on Alippi’s survey but stripped of additions that post-date the basilica’s moment of inception. A regular fenestration pattern is proposed in the clerestory and side aisles on the basis of the traces of remnant windows depicted in early modern views including Figure 3.23 and Giovanni Ciampini’s plate vii from Vetera Monimenta (1690). The pair of void scenes in the fresco cycle above the arcades on the southern side were unknown even in early modern times, hence they remain blank here. |

|

Fig. 2.24 Reconstructed section looking toward the north, ca. 404. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. These are longitudinal sections based on Alippi’s survey but stripped of additions that post-date the basilica’s moment of inception. A regular fenestration pattern is proposed in the clerestory and side aisles on the basis of the traces of remnant windows depicted in early modern views including Figure 3.23 and Giovanni Ciampini’s plate vii from Vetera Monimenta (1690). |

|

Fig. 2.28 Comparison of cones of view from the main door with and without columns at the triumphal arch. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. |

|

Fig. 2.29 Reconstructed view of a hypothetical canopy around Paul’s sarcophagus (in red) with properly positioned floor inscription of Gaudentius and underground sarcophagi (labeled “N” and “O”), ca. 404. The cross-hatched portion includes the Constantinian apse and the hypothetical walls of that basilica. The white portion is the concrete plug poured into the apse to sustain the sarcophagus and canopy. Both the apse and concrete plug were beneath the Theodosian floor (here shown hatched). Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. Axonometric view from the NE that includes the original, Theodosian transept, but also peels away its northern half to reveal: (1) the underlying Constantinian remains; (2) the poured-concrete plug (in white) discovered in the 1850–1854 excavations; (3) the epitaph (and tomb) of Gaudentius (died 389) reported in that position and at the precise level of the Theodosian floor by Vespignani; and (4) two additional (a capanna) tombs labeled “N” and “O” by Vespignani that were located beneath the Theodosian floor, and in close connection to the Constantinian apse. |

|

Fig. 2.30 Reconstructed view of a hypothetical canopy and enclosure around Paul’s sarcophagus, ca. 404. The upper reaches of the mosaic were reset during Pope Leo’s repairs, which may explain why the (Leonine) clipeus of Christ employed in this reconstruction seems cut by the earlier, wider (Theodosian) arch. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. |

|

Fig. 3.2 Reconstructed view of the elevated transept and reconfigured presbytery of Pope Leo the Great, ca. 461. The ciborium over the main altar and the episcopal throne in the apse are hypothetical. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. Floor levels and placement of the epitaph of Theodotus outside the Leonine presbytery are derived from Giorgio Filippi’s excavations. The appearance and even the existence of a canopy over the main altar is based on the continued presence of one at St. Peter’s. The position and elevation of sarcophagi “K, L and M” are based on Vespignani’s scrapbook, Ms 67, fol. 42. The decorated pattern along the interior of the presbytery enclosure is derived from fragments reconstructed by Ranucci and Zorzan. The exterior decoration was painted fake-marble, but too little survives to attempt a reconstruction. The positioning of the papal throne is likely, given that the presbytery probably stretched to the apse. |

|

Fig. 3.4 Modern plaster cast of “PAULO APOSTOLOMART” slabs scaled and overlaid onto “Vespignani Sketchbook,” fol. 11r. The juxtaposition indicates they were larger than they are known to be today. Drawing by Evan Gallitelli. The drawing in Vespignani’s sketchbook is not to scale, but it includes several measurements, some made using as reference point the letters of the inscription or the holes drilled into the slabs. A selection of these measurements was overlaid onto the plaster cast of today’s inscribed slabs to indicate that when the drawing was made during the 1838 dismantling of the main altar, it was discovered that the slabs were far bigger than we know them to be (hidden as they are within the main altar). The important consequence of this discovery is that Leo’s altar – for which they served as the mensa – was also much larger than we once imagined. |

|

Fig. 3.5 Reconstructed view of the altar and presbytery of Pope Leo the Great, ca. 461. The epitaph of Theodotus is just outside the perimeter of the enclosure and the colonnettes on the altar are an alternative hypothesis with respect to Figure 3.2. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. The actual arrangement of the portion of presbytery enclosure beneath the triumphal arch is speculative. The position of the “SALVS POPVLI” inscription on the rim of the new altar is based on my analysis – discussed in Chapter 3 – of drawings in Vespignani’s sketchbook (Figure 3.6 in the book). In this case, an alternative canopy is presented on the basis of a presumed column pedestal atop the mensa in Vespignani’s drawings and a similar solution at the contemporary church of Sant’Alessandro (Figure 3.9 in the book). |

|

Fig. 3.18 Reconstructed view of Pope Gregory the Great’s presbytery from the northeast, ca. 604. The appearance of the ciborium, placement of the throne, and entrances to the crypt are hypothetical. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. The succession of elevated floors in the transept are based on Giorgio Filippi’s excavations. The width and depth of the new altar built by Gregory the Great is based on Vespignani’s sketchbook, fol. 11 (Figure 3.3 in the book). The appearance and even existence of a canopy over the main altar is, again, speculative, but based on the presence of one at St. Peter’s (Figure 3.20). The placement of the northern and southern walls of the presbytery are secured by a foundation wall discovered by Filippi. The eastern wall and the apsidiole are speculative, but based on the presence of an apse and throne at St. Peter’s and in a later iteration of the presbytery still present in the mid-sixteenth century. The existence of two flights of stairs to access the crypt is hypothesized on the basis of ease of use, a similar arrangement at St. Peter’s and on account of the mention of two “blocked doors” in a later version of the crypt. |

|

Fig. 3.19 Reconstructed view of Pope Gregory the Great’s presbytery and crypt from the north east along with archeological finds below grade (in blue), ca. 604. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. The succession of elevated floors in the transept are based on Filippi’s excavations. The width and depth of the new altar built by Gregory the Great is based on Vespignani’s sketchbook, fol. 11 (Figure 3.3). The appearance and even existence of a canopy over the main altar is, again, speculative, but based on the presence of one at St. Peter’s (Figure 3.20). The placement of the northern and southern walls of the presbytery are secured by a foundation wall discovered by Filippi. The eastern wall and the apsidiole are speculative, but based on the presence of an apse and throne at St. Peter’s and in a later iteration of the presbytery still present in the mid-sixteenth century. The existence of two flights of stairs to access the crypt is hypothesized on the basis of ease of use, a similar arrangement at St. Peter’s and on account of the mention of two “blocked doors” in a later version of the crypt. The heights of sarcophagus “A” and “L’” are unspecified, but they must be lower than the presbytery floor, so they are reconstructed as equal to sarcophagus “B,” which is to say 53cm. Incidentally, Vespignani confusingly labels two sarcophagi as “L;” for clarity I have labeled one L and the other L’. The raised transept floor also covered the bases of the triumphal arch columns set on Leo the Great’s transept. |

|

Fig. 3.20 Comparison (at the same scale) of Pope Gregory the Great’s work at St. Peter’s (left) and at St. Paul’s (right), ca. 604. Image by Evan Gallitelli includes reworked drawing of St. Peter’s published by Jocelyn Mary Catherine Toynbee & John Ward Perkins, The Shrine of St. Peter and the Vatican Excavations (London: Longmans Green & Co., 1956), fig. 22. |

|

Fig. 3.21 Reconstructed section through Pope Gregory the Great’s transept, presbytery, crypt, and confessio, ca. 604. Model and image by Evan Gallitelli. |

For images in chapter 4-6, click here

For images in chapter 7, the epilogue and appendix, click here

Return to main page